Callista Buchen

Recovery Effort

A flood of loose-leaf paper swells and overruns the neighborhood drainage ponds, college-rule and wide-rule flying up to people’s foundations, sheets sliding under garage doors. Some basements are threatened. No one can use the intersection. Have you got a pen? my neighbor shouts, over the rustle and slice of paper against paper against house after house. I collect three-ring binders, so I’m in charge, and everyone wants to know where the emergency shelter will be, if there will be enough bottled water and clean socks. Wipe your feet, I say. Welcome. I start handing out bandages and pairs of gloves, while a few towns over they are picking the last of the flowers and talking about fall. There is someone in the corner with scissors cutting out snowflakes. The more intricate the better, I say, as I unload cartons of magic markers, the kind that smell like candy and you remember forever.

-U-

Callista Buchen is the author of the full-length collection Look Look Look (Black Lawrence Press, 2019), and the chapbooks The Bloody Planet (Black Lawrence Press, 2015) and Double-Mouthed (dancing girl press, 2016). Her work appears in Harpur Palate, Puerto del Sol, Fourteen Hills, and many other journals, and she is the winner of the Langston Hughes Award and DIAGRAM's essay contest.

Photo by Kelly Sikkema

Ken Poyner

Picnic

The tyrannosaur emerges onto High Street at the intersection with Court Street. In the hurdled seconds it takes for pedestrians to recognize what has happened, a random man is bitten in half, his half body below the waist falling still giggly to the pavement, the groundless body above the waist methodically mouthed into a more manageable morsel and gagged down the monster’s gullet. Is this a horror materialized from the planet’s far past? The spawn of some mad scientist developed and escaped from one of our historic Olde Towne district homes? People, swallowing their petrifying surprise, begin to run, to haplessly scatter: it is like ants set free in a sugar factory. The smarter prey dash into store fronts, pick establishments with small doors, entryways that a plodding tyrannosaur would find too narrow to squeeze comfortably through. The calm beast looks both ways, determined apparently to take a turn onto High Street, but looking to select a productive direction, perhaps with animal skill judging the likely escape route selected by the more lugubrious of his fickle prey. He cannot eat them all, but possibly it is mere mayhem he is after, the odor of terror, enough fear to swim in. He is too new to our environment for us to know what his real intention is. From windows above the second floor, workers crowd at the glass, their palms pressed flat as though inking an imprint, imagining what of this spectacle tonight they will replay to their children. They conjure how the children will mimic the horror with their slithery jaws grinding and gnashing, their potentially delicious bodies hunched endearingly forward, and not knowing.

-U-

After years of impersonating a Systems Engineer, Ken Poyner has retired to watch his wife break world raw powerlifting records. Ken’s four current poetry and four short fiction collections are available from www.barkingmoosepress.com and myriad places.

Photo by Luca Bravo

Howie Good

Swimming in Oblivion

1

The composer was sticking all sorts of things – bottle caps, tenpenny nails, forks and spoons, tortoise shell combs – in the strings of a Steinway in preparation for a performance. He followed the oft-abused philosophy that if you can’t make art that is popular, you can at least make art that is perplexing. Later when he performed the piece, it would sound to some like a hellish chorus of rackety machines and to others simply like the crackle of gunfire.

2

“No gods, no masters / The revolution will be kingless,” some defiant soul had carved into the wall where anyone passing along the road could see it. I myself have thought about growing a fierce black moustache in the style of legendary brigands, but know deep down I won’t ever actually do it. I lack the necessary nerve. It didn’t disappear all at once, but almost imperceptibly, breath by pale breath, particle by dim particle.

3

It was getting shot in the neck while fighting against the fascists in Spain that had completed George Orwell’s political education. In the after years, the frontline trenches would be filled in and paved over or replanted with trees. The dead in their hundreds of thousands would possess only antiquarian interest for the living, if even that. Sea levels would rise, and labia cleavage become the hot new swimsuit trend.

4

The bomb bay doors are open, the bombs whistling down, the human targets below powerless to flee. We forget the most basic thing as if it were too complicated to remember: no person is safe where any person isn’t.

-U-

Howie Good is the author of FAILED HAIKU, a poetry collection that is the co-winner of the 2021 Grey Book Press Chapbook Contest and scheduled for publication in summer 2022.

Photo by Benoît Labourdette

Allison Xu

The Unthinkable

My azalea stopped growing when my dog Milo died. Sunlight and water lost their charms. Bumblebees and butterflies hovered above her flowerhead for a brief second, then fluttered away and never came back. Her petals turned from peach-pink to pale brown, creased and tattered like rags. Her leaves dried and cracked, hanging listlessly on the darkening stems. “Your azalea is sick,” my neighbor said. But I knew she was dying—from my fingertips, I could feel breath draining from her body. In my mind flashed the image of Milo, who sniffed her when he pranced out the door and wagged his tail as if he had seen a treasure, his muzzle wet from the glinting dew on her blossoms. In the fourth week after Milo’s death, on a night of a rumbling drizzle, all her faded petals and leaves tumbled to the ground, her stems bent like brittle paper straws. I collected all parts of her and buried them next to the mound in which Milo rested. I had a feeling that was where she wanted to be.

-U-

Allison Xu loves writing poetry and short stories. Her work has been published in Germ Magazine, Secret Attic, 50-word Story, Bourgeon Magazine, etc. When she's not writing, she enjoys reading, swimming, baking, and playing with her beagle.

Photo by Vernon Raineil Cenzon, with B&W version added

Cherie Hunter Day

Wranglers

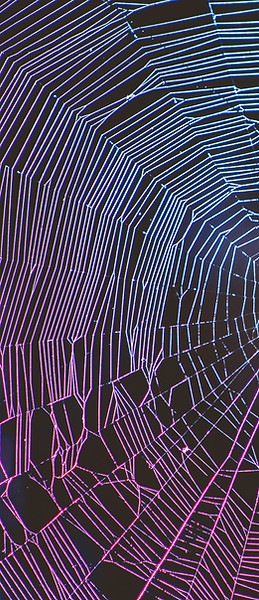

It’s September and the orb-weaver spiders have begun to build their large wheel-shaped webs. When prey blunders into the sticky spiral, it’s quickly subdued and then wrapped in silk. Or in the case of stinging prey, like bees and hornets, they’re wrapped first and then stunned. Some of the spider’s upcoming meals dangle in grey anonymity. The proprietors of the Wood V Bar X Ranch have a similar strategy to advertise their livelihood. They’ve hung a life-sized replica of a beef carcass on their entrance gate. Although the spotlight shines down on simulated flanks, the message is genuine. Welcome, friends!

-U-

Cherie Hunter Day lives in northern California among 17 thirsty redwoods. Her short prose pieces have appeared in 100 Word Story, MacQueen’s Quinterly, Mid-American Review, Moon City Review, and Quarter After Eight.

Lisa Badner

Gemilut Hasadim

(performing acts of loving kindness)

When a new girl showed up in middle school with mostly no hair, the kids all wondered, what was going on. Brain tumor, we soon learned. She had a few scraggly hairs in the back. She was bloated and quiet. My mother told me to be nice to her because that’s what we do. So I was. I spent class breaks with her. I went to her bat mitzvah. Though, honestly, she was too sick by then to know or truly like. I had no ‘before’ with her to grasp or miss. At Christmas time, some seventh grade boys handed her a present. She unwrapped it, excitedly. Only to find, in the box, a hairbrush. I continued to be nice to the girl but I don’t recall saying anything to the boys about their terrible act. I had no clout, no popularity as leverage. After she died a few months later, the middle school principal scolded the class for its cruelty. I wonder if those boys, now men, carry any shame with them. Do they volunteer in pediatric cancer wards? Do they at least send money to St. Jude? If I believed in karma, I’d guess what’s coming to them. That which is coming to all of us, actually. I was kind to the girl. I acted as a friend. But I didn’t cry or feel particularly anything when she died, except maybe relief, so I could play jacks with my friends again during recess.

-U-

Lisa Badner's writing has appeared in Rattle, New Ohio Review, TriQuarterly, Mudlark, #theSideshow, Fourteen Hills, PANK, New World Writing, The Satirist, PING PONG, and others. Her full-length collection of poems, FRUITCAKE, is forthcoming with Unsolicited Press. Lisa lives in Brooklyn.

Rebecca Ressl

Makeshift Years

That summer, my brother and I designed a lopsided baseball field using metal lawn chairs for bases. It was only the two of us, so if you could hit the ball you would make it to first base. And then you would hit the ball again, and run to first base again, as your imaginary self that hit the first ball, invisibly ran to second. Our transparent bodies running base by base thrashing at mosquito wings and tripping over turnip roots. Jumping over the shadows of the laundry line crisscross. That summer, we pushed our past selves forward.

-U-

Rebecca Ressl is a grant writer for community nonprofits and an emerging creative writer from Madison, Wisconsin. Her work can be found or is forthcoming in Masque & Spectacle, Sky Island Journal, Spellbinder, and Second Chance Lit.

Photo by Mike Bowman

Rachael Clyne

The Tree Was Astonished to Be in the Kitchen

Its mossy scent mingled with the fried bacon smell. Rooks fled through the open window, plastering it with gobbets of droppings, dazed insects crawled from bark, scuttled across worktops to find melamine crevices. Some tumbled down the plughole. Branches crammed every cranny; it was impossible to move. We hacked our way to the sink with a bread knife. Why in Earth did you bring me here? demanded the tree. It’s alright, we’re eco-friendly, we want to be closer to nature, we replied. Would you like a hug? The tree struggled to steady itself, roots slapping and sliding on the tiled floor. Water, croaked the tree, we offered it a glass, but it just guzzled straight from the tap. I need light. Don’t worry, we have one of those special lamps, if you need it. Gradually, we learned to live together. We used branches to hang pans and tea-towels. Mycelium networks slipped through the grouting and fine roots found their way down through the foundations, holding everything in place.

-U-

Rachael Clyne is from Glastonbury UK, and is widely published in journals and anthologies. Her prizewinning collection, Singing at the Bone Tree (Indigo Dreams), explores our broken relationship with nature. Her pamphlet, Girl Golem (www.4word.org), concerns her Jewish migrant heritage and sense of otherness.

Photo by Bob Blaylock

.jpg)

Jeffrey Thompson

Lusk

One summer on the way back to Fargo our station wagon broke down outside of Lusk, Wyoming. We were stranded for several days waiting for a part. What was there to do in Lusk? Look into a crushed car that had been towed to the filling station. The driver was killed. Her guts were all over the seat, like a smashed watermelon, seeds and all. One night my dad took us to a rodeo. On the way back to the motel my brother and I were fighting. Trying to think of something bad to call me, he stumbled onto the word pimp. Dad said no, don’t ever use that word. It’s the worst thing you can call somebody. That wasn’t in Lusk, my brother told me, 40 years later, after dad’s stroke. That was in Fargo, at the fairgrounds after the stock car races. I could have sworn it was Lusk, where there was nothing else to do.

-U-

Jeffrey Thompson was raised in Fargo, North Dakota. He was educated at the University of Iowa, where he studied English and Philosophy, and Cornell Law School. He lives in Phoenix, Arizona, where he practices public interest law. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Neologism Poetry Journal, The Main Street Rag, and Tipton Poetry Journal. His hobbies include reading, hiking, and photography.

Photo (detail) by Daniel Lloyd Blunk-Fernández

Meg Pokrass

Wings in the Living Room

When you are gone there are wings in the living room. They beat in the living room and I worry all day long. Sometimes I think about my father who was all alone, sitting in the house waiting for us to come home. I wonder about him and now that I’m his age I let myself say it. Please come home, I say, to the empty living room. I stare at myself in a cup of tea, seeing how milky I have become, how weak. I finger the phone and I remember that there is a world of other men who will never come home to me. I have been loving the kind of man who will never come home to me since I was a little girl. My mother had wings, or at least it seemed she did, she flew all over my childhood trying to fix the holes we made. I’d clap for her and the two of us would stare up at the palm trees and feel like it wouldn't matter. We had trees that looked like tall leading men.

-U-

Meg Pokrass is the author of eight collections of prose and the Founding Editor of Best Microfiction. She lives in Inverness, Scotland.

Photo by Josh Miller

Thad DeVassie

A Man and His Cow

at Lunchtime

A man and his cow saunter up to a Chipotle near the city limits for lunch. The man steers his cow into a parking spot and ties a leash hanging from the cow like a necklace to a red fire hydrant. The man goes inside to order chips and salsa, a small vat of lime-infused rice, a platter of beans and vegetables with guacamole, and the new plant-based chorizo that is all the rage. Naturally the people in line are fuming at the man’s long order during the lunch hour, but are distracted by the sight of an enormous cow in a parking space tied to a fire hydrant. “No foraging today, girl” the man says, walking outside with his order. “Here’s a little something for all four stomachs.” The cow chows down and then chews her cud in satisfaction. The entire lunch-hour staff stares out a side window to see this carnival-like spectacle. Someone questions aloud, “Is that a Jersey or a Holstein?” followed by “I dunno, what do they call the Dalmatian of cows?” The man, now ready to roll with his cow, gives a polite nod and subtle finger point to the staff, signaling he’ll be back in an hour or two for the steak carnitas once his cow is out on pasture.

-U-

Thad DeVassie is a writer and painter who creates from the outskirts of Columbus, Ohio. He’s authored three chapbooks including SPLENDID IRRATIONALITIES, which was awarded the James Tate International Poetry Prize in 2020. Find his words and paintings @thaddevassie.

Photo by Ashim D’Silva

.jpg)

Cyril Wong

Fuck the Ontologists

Shin Dong-hyuk was not to know love in a North Korean labour camp, where he snitched on friends with whom he had played, and on his mother who fed him, for survival; he met its nature, a journalist writes, only long after stumbling into the free world through an electric fence charring both his legs; free or not to love and not love—are we asking the right question here, for what is love without its conditions; is it still love—and if nothing exists, what is nothing then, or however we choose to name it; what kicks away the mind’s roof when we meet it for the first and last time, if it is not love, or anything we have ever known?

-U-

Cyril Wong is a poet and fictionist in Singapore. His last book of poems was Infinity Diary, published by Seagull Books in 2020. His poems have appeared in Atlanta Review, Poetry International, and Poetry New Zealand. He runs and founded SOFTBLOW Poetry Journal.

Photo by Patrick Hendry

Mikki Aronoff

The Mistress of Dreams

The Mistress of Dreams watches from afar as your car veers to the side of the road, slides into the ravine. She sees you struggle to open the door, then tumble into a ditch. Your teeth are packed with mud, your feet are stuck in sludge. She pretends she’s not the one who shot out your tire, arrives later, like Roadside Assistance. The Mistress wipes your bewildered brow, hands you a basket of fire, a sieve of water, asks you to choose. You can’t have both. But you can’t speak. The mud in your mouth is hard as clay.

*

The Mistress of Dreams yanks and tugs at her girdle, shimmies its rigor. This makes her feel kind, and she drops a lover into your bed, your sheets freshly laundered, your phone silenced, your freshly-shaven legs parted and waiting. She strikes a match, lights the patchouli candle in the bedroom window, doesn’t notice the wind stirring the curtains. You frown at the men arriving with hoses. They don’t fit the ideal of firemen. Or lovers. They would never make the calendar.

-U-

Mikki Aronoff has work in Flash Boulevard, New World Writing, MacQueen’s Quinterly, ThimbleLit, The Phare, The Ekphrastic Review, The Fortnightly Review, and elsewhere. Her stories and poems have received Pushcart and Best Microfiction nominations.

Photo by Lux Graves

Lyndi Waters

Rethinking an Innocent Omission While Accompanying My Friend to the Doctor

His office is a heretofore never-seen-in-nature green. I fully expect to hear birds burst into song any minute now. Fluorescent lights flicker, click, disturb the rain forest atmosphere. I can’t help but stare at Dr. Kendrick’s fingers as they dart across the keyboard. First thing Wednesday morning they will be working inside my friend Mary’s abdomen. Images settle on the computer screen, flashes of behind-the-scenes activity in the City of Mary. It doesn’t seem right somehow, Kendrick’s impatient racing through fuzzy black and white scans of Mary’s main drag, passing a church, a liquor store, the Chamber of Commerce, and a car wash. His annoyed, eye-twitching expression is that of a man who wants to find a five-star hotel, but all he can see is a fleabag ramshackle dive with a neon MEDICARE sign blinking above it, elderly street walkers haunting the corner of Hip and Spine—their faces lit fuchsia, yellow, fuchsia, yellow again. My cousin Cami is the surgeon’s housekeeper. She tells me things. Last week at Bingo she said this steel sliver of a man spends his solitary evenings listening to Yo Yo Ma and preening a pride of Himalayan cats. “Sometimes he drools and dangles a little live mouse over their heads, then smiles when they bat it with their paws right before they, well, you know,” she said. Cami isn’t reliable. Later that night Mary asked “What did Cami have to say about him?” I may have mentioned something about the good doctor being a music lover.

-U-

Lyndi Waters is a winner of the Frank Nelson Doubleday Memorial Writing Award, the Eugene V. Shea National Poetry Contest, and is a Pushcart Prize nominee. She lives in Wyoming with her two dogs. The chickens live outside.

Photo by Adi Goldstein

Ian Willey

Ghosts

Strange things happened when our kids were in their teens. We’d find tiny organs in egg yolks, sometimes vestigial limbs. Late at night you could hear doors opening and closing from the room upstairs when the room upstairs had been vacant for many years. And then there were the weeds along the river, how we’d find bunches of them neatly braided, forming little arches beneath which sparrows held wedding ceremonies. All this stopped when the kids moved out. Eggs are just eggs, and the weeds by the river have never been more unkempt. The sparrows have gone their separate ways. Some people have moved into the room above us. They never make a sound.

-U-

Mrs. Sonnenberg, Ian Willey's first-grade teacher, wrote the following: "Ian is basically a serious little boy but appears to be happy and comfortable in our group. He is showing more self-confidence and is well liked by his peers." (Editor's Note: We decided to put Mrs. Sonnenberg's name in boldface instead of Ian's because we know Ian and we know he would want it this way. And he is showing more self-confidence.)

Photo by Hans Veth (remixed by Unbroken staff)

Jeff Burt

Crying Uncle

In hollows and heartland crops the boy grew, and one day along came his uncle and a cloud during a drought. The uncle talked to the cloud of his need for a drink, and the dirt cracking in thirst—and a thunderhead formed like a god speaking and soon it started raining all over—the boy believed the uncle’s words squeezed water right out of the sky. The boy moved to a city, in a particularly corroded part of town near a freeway, an unused railroad, and a row of houses his mother didn’t want him near, and one day that uncle came along cooing to rusted ribbons of tracks and the boy heard a gunshot. Soon bullets were flying and a train with empty cars crawled down the tracks for the first time in eleven years between the gunfire and them, and he believed his uncle wooed that train down the tracks, called for it with tremolo and falsetto. Even now, as a man, he remembers that summer when his mother was dying of cancer, knuckling under to pain and buckled by poverty. Even now he cries for his uncle to make it stop.

-U-

Jeff Burt lives in Santa Cruz County, California with his wife. He has contributed to Per Contra, Gold Man Review, Williwaw Journal, and Brazos River Review.

Photo by Antoine Beauvillain

Preeti Talwai

Home Remedies (from my mother)

Drink more water. Don’t worry so much. Don’t eat so fast, chew thirty times. Don’t think so much about it. Don’t get stressed out, learn to be happy. Don’t keep saying ulcerative colitis, you’ll trick your mind into being sicker. Don’t think negatively. Don’t assume you’re going to end up like your aunt. Don’t tell anyone, you still need to get married. Don’t eat or drink while standing. Don’t blindly trust Western doctors, they just want your money. Don’t shout Amma like that, don’t get hyper at me. Don’t eat peanuts, they create heat in your body. Don’t tell him yet, he might not want your body. Don’t sit so much. Don’t get annoyed, don’t you see I love you. Make sure the water is warm.

Photo by Dendy Darma Satyazi

Preeti Talwai

Diagnosis

Chronic means persistent, means recurring, means lifelong. Means forever. At twenty-one — hung over on Propofol in a periwinkle gown, spine dotted with goosebumps, thighs sweat-stuck onto crunchy exam-table paper — forever means the three months until graduation. The nice nurse, the one who can find my tiny veins, slips on gloves as she explains there is no. known. cure. Latex snaps between each word. Her eyes say it is Big News. But I forgot to borrow a calculator for the final tomorrow. I need to get coins for laundry. And I’m feeling like tacos for lunch.

-U-

Preeti Talwai writes from the California coast, where she also works as a researcher in the tech industry.

Photo by Clay Banks (remixed)

Richard Baldasty

Through Wondrous Doors

In the grand hotel, I felt a breeze of dreams cross the lobby, dart to the glass dome above the mezzanine. My ancestors were sitting in high back chairs, staring at nothing as befits custodians of former worlds. I watched as my great, great grandmother artfully removed her name, then her face, and put them on a tray extended toward her by a brisk young man in hotel livery. I felt he might also be me, that the rasp of his voice would tell me for certain. But when I signaled to him, he turned away in silence, then into air. I went to the desk, returned my room key, paid the bill with beautiful quotations. I asked the concierge about calling a taxi. There were none, she said, everyone at home for the sacred holiday. So I got on a panther and left the way I came.

Photo by Tim Mossholder

Revenant

Richard Baldasty

A car pulls up. A man appears, walks near. The car, robin egg blue; so too the man. The street, bright and slick, shines with sunlight on ice. The man reaches out, touches the car, spins it like a top. Round and round, round and round. Three people get out of the car: dizzy, tipsy, trippy, they cling to the blue man. They have missed him so much since he died. Grief reigned heavy and opaque, bone aches of longing and loss, wild howls into pillows, heart thorns in the dark. Now he’s back strangely new in robin egg blue yet familiar in his tricks, hugging them, whirling them round. They may begin to feel better soon, maybe even today. They’ll not be able to keep him, but when he leaves again his song on earth, this time, will stay.

-U-

Richard Baldasty, poet and collagist, lives in Spokane in eastern Washington state. Recent work appears in Hole in the Head Review.

Photo by Aaron Burden

Ron Hartley

Cannonballs

Winter loosened its grip and the old widower emerged from under his mantle of despair. He splurged beyond his means in the way of an in-ground swimming pool, a spring-action diving board and a forty foot flag pole with the gold-plated figurine of an eagle on top. Birdsong accompanied his strokes through water in summer days as we watched and waited in the alley and street. His signal was a green flag raised to the eagle’s claws and we came in swimsuits and innocence. We came to imitate each other’s half realized flips, midair twists and smashing cannonballs. We came in the clamor of laughter and screams, as if neighbors wore earplugs and didn’t suffer the sound, as if cops were never called to silence the sound. The pool got drained into time and time did what time does best, reducing decades into the likes of a millisecond. The kids are grown and moulded into creatures of the grind, many of us the worse for wear. But I can still remember the gold of an eagle that gleamed in the sky, and that plunge into an aquamarine silence illumined by the sun.

-U-

Ron Hartley was an art director at four New York ad agencies. He’s into writing these days and has had stories published in The Sky Island Journal, Mobius, Fiction on the Web, Literary Juice, and others. He lives in Brooklyn.

Photo by Jose Antonio Jiménez Macías

Colette Parris

Up Close and Personal

Scientists say that in another 250 million years or so, Pangea 2.0 will make an appearance. I won’t be there to see it, and the way things are going, there’s a high probability that neither will anyone else. Nevertheless, I find myself constantly contemplating this scenario. I visualize the moments when Canada slams into Greenland (with apologies), Argentina hip checks Namibia, France washes up on the Jersey Shore, and Australia crashes India’s party. I imagine Everest-sized tsunamis flooding the deserts, a sun blinded by the ash of instant volcanoes, and deafening roars as the plates slide home. I picture the dust eventually settling, the survivors pushing past warranted hysteria and taking stock of the new world order. For once, there is no need for translation and no basis for dissonance. Everyone left has the exact same thought at the exact same time in every possible language. Namely, “Well, this is awkward.” Their brief unity is a bright and glorious thing.

-U-

Colette Parris is a Caribbean-American attorney. Her poetry and prose can be found in Streetlight Magazine, Vestal Review, BigCityLit, Thin Air Magazine, Lunch Ticket, Burningword Literary Journal, and elsewhere. She lives in Westchester County, New York.

Photo by Philipp Ollmann

Robert McDonald

Much the Same Countenance

One day I heard that the piano tuner had died—walking pneumonia complicated by decades of heavy smoking, although the piano tuner was still a young man. I’d struck up a conversation with him one night, we were both drinking at the neighborhood bar. And I might have seen him again, except that he was coming to the end of his schooling, and soon would move back to the city of his birth, unless, as he said, someone gave him a good reason to stay. Like getting a boyfriend, he said, or money. But I was broke, and also just stepping through the doorway to a life with someone else, and the piano tuner did not press his case. Via email he told me that he learned his tools, he practiced his tuning, and he practiced his pieces. I never heard him play. After he died, I tried to imagine his slender fingers, his charming stutter, and the expression on his face when he played a favorite and difficult selection, much the same countenance as a person lost in the act of love.

-U-

Robert McDonald lives and writes in Chicago, where he works at an independent bookstore. His work has appeared recently in Bending Genres, Elsewhere, and Atticus Review, among others.

Photo by "House Rent Boogie," seller on Internet.

.jpg)

Benjamin D. Carson

The Man Who Shot at Birds

I heard it told of a man who shot at birds, his porch wrecked with shells spit from his gun. His hooked nose and gimlet eyes flush against the stock, he aimed for their wings, their beaks, and he aimed for their eyes. He liked to watch them flail, he said, a ballet of feathers, as they fell, notes on an atonal, descending scale. He said he liked to hear a clipped song sung by a nicked tongue, while they flew and flew and flew, blind. Wounded, he’d say, is just as good as dead. And I heard it told that when he died, his body still warm, his arms splayed like plucked wings, a chorus erupted, a dirge, and the trees pulsed with a murder of crows.

-U-

Benjamin D. Carson lives with his dog Dora on the South Shore of Massachusetts. His chapbook, We Give Birth to Light: Poems, was published by Finishing Line Press in June 2021.

Photo by Ospan Ali

Unbroken is edited by Ken Chau, Dale Wisely, Katherine DiBella Seluja, Tom Fugalli, Kelli Goldsmith, and Tina Carlson. Roo Black is founding editor emeritus. Our staff dentist/spiritual advisor is the Lt. Col. J. Benton II, D.D.S. Our thanks to the contributors to this issue and all who submitted their work.